by Professor Derek Fraser

(A shortened version of a lecture given on board Queen Elizabeth as part of the Cunard Insights programme January 2014)

Slavery is as old as civilisation itself and many ancient Empires, including Egypt, Greece and Rome, were built on slave labour. However, in the 17th and 18th centuries slavery took on a new more systematic form, in the wake of the voyages of exploration to and colonisation of the Americas by Europeans. The fertile land of the New World generated a demand for labour which far exceeded the supply of both indigenous peoples and migrants. Africa seemed to promise an unlimited supply of labour which the colonies needed and so the infamous triangular slave trade developed. Ships from Europe would take manufactured goods, including basic armaments, to ports in West Africa. There the products were offloaded and traded for African slaves, brought to the huge slave warehouses by unscrupulous traders, often Africans themselves. The “middle passage” transported the slaves to North and South America in horrendous conditions. Many suffered serious illness or died during the voyages and resistance by the slaves was common. Once in the Americas the slaves were either handed over to owners who had previously purchased them or sold in the specially designed slave markets. Many of the buildings where slaves were sold still exist, especially in the West Indies. In the third leg of the triangular trade the produce of the New World, including sugar, tobacco, spices and later cotton, was transported back to the old European world, contributing to rising living standards and generating great wealth.

The slave trade was a massive operation on a large scale. Slave traders transported some 11 million African slaves across the Atlantic, with Portugal the most active with 30,000 voyages and its colony in Brazil receiving the most slaves, 4 million. Britain, with its naval dominance, was also a prime mover with 12,000 voyages transporting nearly 3 million slaves to the West Indies and North America. The ports of Liverpool, Bristol and London grew on the slave trade and much of the wealth of Georgian England derived from the slave trade and from the ownership of the slaves who worked in the great plantations in the colonies. Indeed, one of the reasons Britain was the first country to have an Industrial Revolution was the ready availability of capital, which largely came from slavery.

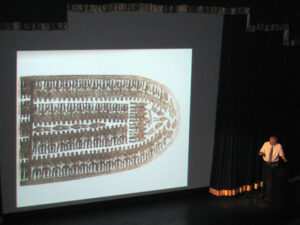

The slave traders and owners, who formed a powerful vested interest in 18th century British politics, often defended themselves by saying that they were converting heathen slaves to Christianity and thereby saving souls. It was, therefore, ironic that religion was the prime mover in the development of a powerful and ultimately successful anti-slavery campaign. Starting with Quakers and spreading to a wide range of Evangelical Christians, a movement grew which transformed the leading slave trading nation into abolition in the space of 20 years. Growing publicity about conditions in the slave ships prompted a sensitivity to suffering, which was made more acute by emerging ideas of liberty and equality in the Age of Reason. Sketch plans of the slave ship Brooks, which was designed for the sole purpose of carrying slaves, shocked public opinion when it was revealed how slaves were crammed so closely together in the holds that they could not move. The Zong atrocity also prompted outrage, when 133 slaves, some of them manacled, were thrown overboard to save a foundering ship. (This was the subject of Turner’s later painting The Slave Ship). The case later emerged in the British courts as a disputed insurance claim – the murdered slaves were property lost in a storm and of no more significance than a barrel of rum or a bale of cotton.

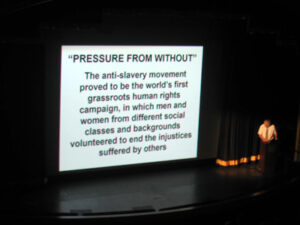

In 1787 the Society for the Abolition of Slavery was founded by activists who were mostly Quakers. Support quickly grew and there were many public meetings, petitions and pamphlet literature against the slave trade. It was believed that to focus on the trade rather than slavery was more likely to succeed and that once the supply of new slaves was cut off, it was likely that the conditions for slaves themselves would improve. The anti-slavery movement was widely based both socially and geographically and was one of the first popular movements to involve women, normally deprived of taking an overtly political role. Some male campaign leaders had a jaundiced view of female participation and frowned upon women speaking at meetings. Hence there were over 100 female only abolitionist societies across the country. The whole campaign was what we would now call a human rights movement.

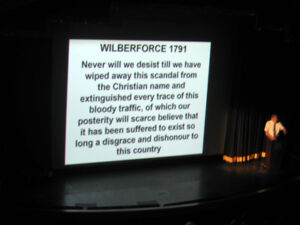

One of the most active campaigners was Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) who tirelessly travelled round the country lecturing on the evils of slavery. He carried with him his famous box, which contained artefacts produced by African craftsmen, to show they were capable, and frightening examples of the tools of restraint used by slave traders and owners. He realised that the campaign needed an active Parliamentary leader if they were ever to get legislation through and he persuaded the Evangelical William Wilberforce (1759-1833) to take on that role. It is likely that the slave trade would have eventually been abolished, but the speed of abolition and it manner of success was largely due to Wilberforce’s commitment and oratory. Wilberforce hailed from a wealthy merchant family from Hull which had made its fortune in the Baltic trade. He was MP for Yorkshire, the biggest and most prominent constituency in the country. From that base he was able to conduct a relentless campaign in Parliament, attacking the slave trade as a moral outrage and a dark stain on Britain’s reputation. The campaigners fed Wilberforce with detailed information which he then used in his powerful speeches to the House of Commons.

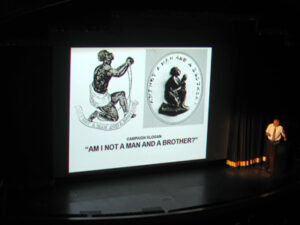

One of Wilberforce’s allies was the pottery magnate Josiah Wedgwood, who made porcelain plaques and pots, which prominently featured the campaign slogan “AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER?” These and other campaign tokens and literature featured an image of a chained negro slave and it was the testimony of former slaves which added poignant personal stories to the growing body of damning evidence. Most famous of these was Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiography published in 1789 became a best seller and was widely read. Wilberforce had a layered wooden model made of the slave ships Brooks which he used in Parliament to shock the doubting MPs. He introduced an annual motion for abolition, gradually attracting increased votes in the House of Commons, which was regularly inundated with petitions signed by tens of thousands of people. Wilberforce was close to William Pitt the younger, who as Prime Minister supported abolition but lacked a majority to get it through. In the event Pitt did not live to see Wilberforce’s crowning achievement when in 1807 Parliament finally legislated to outlaw the slave trade. Though in the middle of a war with Napoleon, Britain committed it navy to police the slave trade which it was still doing 70 years later in places such as Zanzibar.

Britain basked in the moral high ground of abolition and Wilberforce was feted as a great reformer. However, the campaigners were disappointed to find that, though the slave trade itself had been abolished, the condition of slaves in the West Indies plantations did not improve. Hence in the 1820s the anti-slavery campaign was re-launched, this time with the clear aim to free the slaves. Wilberforce resigned from Parliament in 1825 on age and health grounds, but remained in close touch with the campaign and made speeches in the country. The reforming Whig government of Earl Grey finally abolished slavery in the British Empire in 1833, partly influenced by the ferocity of a recent slave rebellion in Jamaica. By that time a new form of slavery was the focus of an alternative campaign. The great Tory-Radical reformer, Richard Oastler, coined the phrase “Yorkshire Slavery” to describe the little children who worked long and dangerous hours in the new textile factories. Oastler mocked the hypocrisy of mill owners who actively supported the abolition of slavery overseas, but who ignored the slavery on their doorstep. In fact, the same parliamentary session which passed the slavery legislation also passed an important Factory Act, to protect children exploited in the industrial regions of the newly industrialised Britain.

There was a bitter price to pay for the abolitionists, since a condition of reform was that the slave owners were to be compensated. Parliament accepted that slave owners had invested heavily in the purchase and provisioning of slaves, that they had in effect been deprived of a property asset. Parliament provided £20 million for the slave owners as compensation for allowing slaves to go free, roughly £12 per slave. Reformers were forced to accept that there was no other way to free the slaves, though they strongly denied that human beings were a species of property. Other nations followed suit and abolished slavery, but over a long period and, of course, it took the Civil War to achieve this in the USA. Sadly, forms of slavery still exist in our own times, often associated with people trafficking.

———————————————-

The lecture was part of a series given by Professor Fraser on “Those Who Changed Their Worlds”. The other titles were

- Captain Cook and the Map of the World

- Lenin and the Russian Revolution

- Franco and the Spanish Civil War

- Churchill and the Second World War

- Gandhi and Indian Independence

- Thatcher and British Renewal

fotos: Johanna Renate Wöhlke